Nick Duerden recalls his first – and best – school trip to a farm run by writer Michael Morpurgo and his wife, Clare, who have given thousands of inner-city children a taste of nature since the 1970s, Nick Duerden

I was 10 and it was my first school trip – my first time away from home. It was to Nethercott farm in Devon, where, our teachers promised us with a certain sinister relish that we would be working as farmers for a full week. We were city children, urban ones, with at least some of the attributes that such a term implies. We lived on council estates, mostly, and many of us had never seen animals that weren’t cats and dogs (and, out by the bins, rats), much less such wide-open spaces. We had no idea, consequently, what working as farmers would really entail. But, with the misplaced confidence typical of all 10-year-olds, we reckoned it would be a doddle. Bring it on.

My mother, though raised in Milan, was born in the former Yugoslavia, in a tiny village where all anyone did was toil the land. We visited once, a year before my farm trip, and stayed with distant relatives. I remember stout women with moustaches and muscles, who found much mirth in my ignorance about what a hoe was and quite how to use it, and thought me sweet when I refused to wring our imminent dinner’s neck – an unsuspecting chicken – much less pluck it afterwards.

It was my mother who, a year later, insisted that a trip to a working farm would do me the world of good. Initially, I didn’t want to go. I thought I’d hate it. And I dreaded being apart from the television for quite so long. “Nonsense,” she said. “You’ll love it.”

Nethercott, a couple of hours away – but a million miles from Peckham – was beautiful and enormous. Nature, of the kind we had only seen on TV, was everywhere: trees, hills. More trees. A rumour, at night, of bats. And there was so much to do. In the mornings, we had to feed the hens and pigs. We had to milk the cows and groom the horses. After lunch, we had to clear the fields of stones (they were big fields), sweep the stables, build bonfires and plant trees. This was backbreaking labour. I remember being woken before dawn to watch lambs being born, and I had so much fun and was so consistently stimulated that I didn’t miss home once.

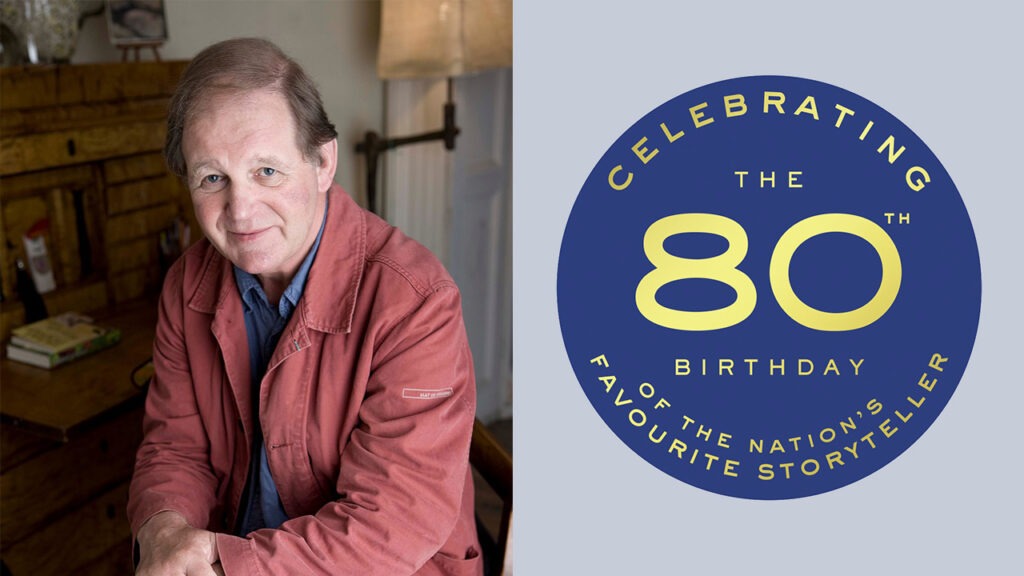

Most evenings, after supper, we would gather in the grand front room around the open fire, while our host, a farmer called Michael, would read to us, his wife Clare by his side. This Michael was a writer, too, it seemed, and he would read to us from his works in progress. Among these, in 1979, was a manuscript called War Horse. I would like to say that I listened keenly to this future classic, but Joe Jennings was busy whispering in my ear throughout and I was too busy attempting to make pre-adolescent eyes at Hazel Harper to pay it much attention. Fool.

I would go on many more school trips, but the years have done their best to obscure the finer details of most of them. It is my visit to the farm that I remember most vividly and the one that now, as a father, I would most like my daughters to go on, should the opportunity arise.

It might well do for, a generation on, Nethercott still thrives, providing inner-city children with a wealth of rich, rural memories. When I speak to Clare Morpurgo about it now, she tells me that all is pretty much today as it was then, except that they had to get rid of the pigs after the foot-and-mouth scare, and there is no longer an open fire in the grand front room.

“Health and safety,” she says. “It’s a wood-burning stove these days.” Farms for City Children was dreamed up by Clare and Michael Morpurgoin the mid-1970s. Back then, the thirtysomething husband-and-wife team were teachers, but both were stymied, says Michael, by far too much staff-room politics, their ideas all too often ignored. One such idea was to offer children with an absence of nature in their lives the chance to experience it at close hand. “We were very idealistic about it,” says Michael, “and convinced that such experiences were the right of every child.”

They did little to further their dream until Clare was left a legacy by her father, the publisher founder of Penguin, Allen Lane. They invested in an old country house with land in the tiny Devonshire village of Iddesleigh, and started to spread the word among schools. There were, initially, many deaf ears, and the Inner London Education Authority was suspicious. While they could comprehend the appeal of, say, an adventure holiday – climbing, kayaking, and the like – the notion of a working holiday for kids simply didn’t compute. What sort of child would want that?

“That was the whole point of it, though: the intensity,” Michael says. “But they weren’t convinced.” This shouldn’t have surprised them, he suggests. “We were, after all, two rather fresh-faced, silver-spooned people. We must have seemed rather patronising.”

But their conviction won out, and in 1976 Nethercott opened its doors to a single school, from Birmingham. A year later, nine signed up and by 1979, Nethercott was welcoming children from around the country for most of the year.

After the inherited money ran out, Farms for City Children became a registered charity (raising £350,000 a year), and over the next three decades would open another two farms, Wick Court in Gloucestershire, and Treginnis Isaf in Pembrokeshire (they are scouting locations in the north-east of England for a fourth). Every year, more than 3,000 new schoolchildren arrive, bringing with them wellies and much anticipation.

Liz Owens is the charity’s chairwoman. A former headmistress, her last post was at the Charles Dickens primary school in Borough, south-east London. “It was failing when I joined, and failing miserably,” Liz recalls. “I’d met Michael [Morpurgo] years earlier, and he told me about the farms then, which I thought such a good idea. I was adamant about signing our school up to it.”

During her eight years as head there in the mid-1990s, she organised successive trips to Wick Court. When she retired, the Charles Dickens was one of the 10 most improved schools in the country. To this she attributes, at least in part, their annual farm trips.

“A lot of our children came from very difficult family situations, and were subsumed in all sorts of troubles that often required of them to grow up quickly,” she says. “Being away from home permitted them to simply be children and, in every case, they absolutely loved it. They came out of their shells – they came alive.”

The Morpurgos are no longer quite so hands-on, but Michael, who is now one of the world’s bestselling children’s authors, believes the farms initiative is his greatest achievement. “It was always just so fascinating, and rewarding, to watch the children react to it all,” he says.

“Many, for example, had never experienced proper darkness before, so walking down to milk the cows on a winter’s night was for them a daunting process. Working in cold conditions, too, and often in discomfort, with sacks over their shoulders to feed the sheep when the snow was driving into their faces – these situations tested the children, but they wanted to be tested. They loved it,” he says.

I certainly did. Nethercott farm was my first school trip, and also my best. It taught me so much. It taught me that there is little to compare to witnessing a newborn lamb take its first unsteady steps. It taught me that I was emphatically not – and am still not today – cut out for physical work. And it taught me that cleaning out the dairy with a stiff broom while all around you the cows continue to shit with careless abandon is a punishment that no 10-year-old boy can quickly recover from.

When I recount this to Clare Morpurgo now, she laughs. “Oh, we tried to make cleaning out the cow poo fun,” she says. “Didn’t we succeed?”

She and her husband may have succeeded in many things, I tell her, but in this, I’m afraid, no, they didn’t.

• For more information, visit farmsforcitychildren.org

Nick Duerden

The Guardian, Saturday 12 May 2012