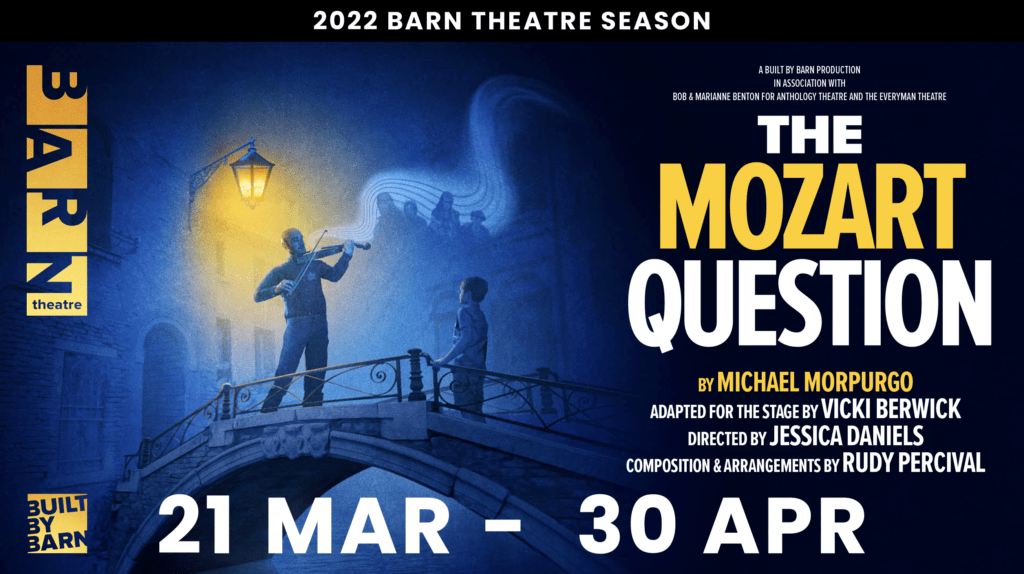

Michael Morpurgo is joined by violinist Daniel Pioro and The Storyteller’s Ensemble to perform a unique adaptation of his book, The Mozart Question. Together they interweave words and music, to tell his haunting tale of survival against the odds, set against the background of the Holocaust.

Simon Reade adapted and directed the performance and shares his thoughts on the project:

‘Michael Morpurgo’s stories move from happiness and joy to human catastrophe in an inkling. He tells his tales through the eyes of adults and the eyes of a child – often one and the same, simultaneously. His writing is intensely dramatic, his characters endure extraordinary psychological journeys, and he is unflinching in his pursuit of emotional truth. This, combined with characteristic exuberance and joie de vivre, is what makes his work so theatrical.

The Mozart Question is about a performer, a musician, so it’s appropriate to take the story from the intimacy of its relationship with one reader and expose it to the shared experience of an audience. We all bear collective witness to this powerful story: to a Europe devastated by war, to the ties that bind parents and their children, and to the sublime redemption offered by exquisite classical music.’

Michael Morpurgo gave some insight into his story and why the adaptation was written to be performed in cathedrals:

‘It is difficult for us to imagine how dreadful was the suffering that went on in the Nazi concentration camps during the Second World War. The enormity of the crime that the Nazis committed is just too overwhelming for us to comprehend. In their attempt to wipe out an entire race they caused the death of six million people, most of them Jews. It is when you hear the stories of the individuals who lived through it – Anne Frank, Primo Levi – that you can begin to understand the horror just a little better, and to understand the evil that caused it.

For me, the most haunting image does not come from literature or film, but from music. I learned some time ago that in many of the camps the Nazis selected Jewish prisoners and forced them to play in orchestras; for the musicians it was simply a way to survive. In order to calm the new arrivals at the camps they were made to serenade them as they were lined up and marched off, many to the gas chambers. Often they played Mozart.

I wondered how it must have been for a musician who played in such hellish circumstances, who adored Mozart as I do – what thoughts came when playing Mozart later in life. This was the genesis of my story, this and the sight of a small boy in a square by the Accademia Bridge in Venice, sitting one night, in his pyjamas on his tricycle, listening to a busker. He sat totally enthralled by the music that seemed to him, and to me, to be heavenly.

I grew up as a schoolboy under the shadow of Canterbury Cathedral, singing in its choir and cloisters, went to communion there in the crypt every Sunday morning, so a great cathedral is part of my being. Each is different, but each is a magnificent statement in stone and stained glass, of faith and hope, and the men and architects who built them, inspired by faith. They built them for worship, for music and song, for the gathering of a community, to pray and to contemplate.

Of course, I do not know York as well as its sister church in Canterbury. It is not familiar in the same way, but every time I have been I have been overwhelmed by its beauty and magnificence.

To play our music and tell our story in this great building is a great honour, and in a way, utterly appropriate. The story, in a way, is one that reflects the best aspirations of man and his worst degradation. And the music in the concert reflects this too. But in both music and story, redemption wins through.’

This adaptation of The Mozart Question is suitable for ages 8+.